Grace and Action in the Path of Spiritual Attainment

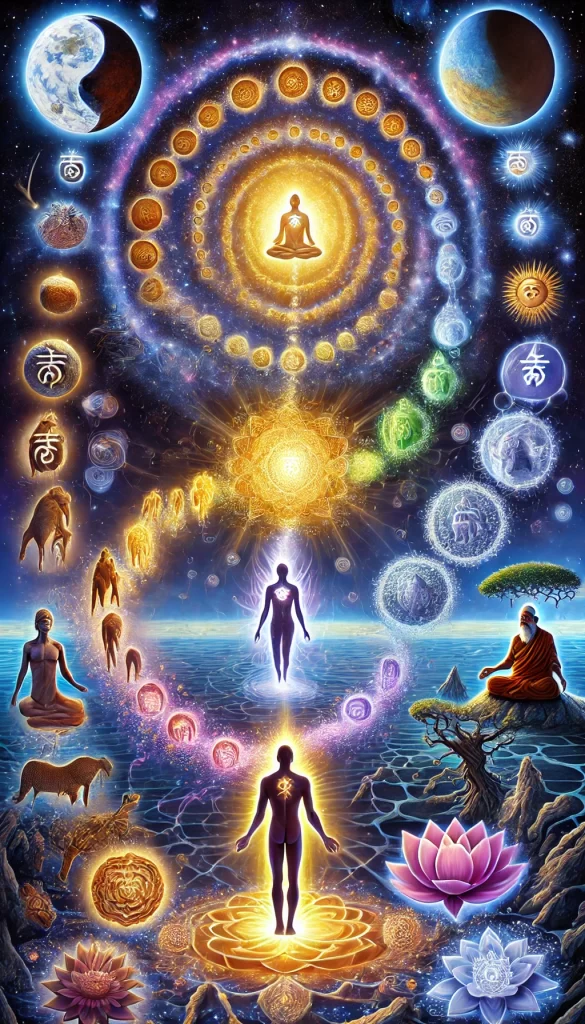

The ultimate goal of human life in the path of spirituality is to attain the Divine, to realize Bhagavān. For this attainment, one must take recourse to appropriate means. As long as the aspirant retains the identification with the body (dehābhimāna) and acts according to the sense of doership (kartṛtvabodha), it is difficult for them to rely on any means other than karma (action). The tendency of desire (kāma-pravṛtti) arises from ego (abhimāna). Every embodied being performs actions at every moment. It is impossible to be free from ego while dwelling in the state of ego; hence, skill in action is required. This skill is yoga—”Yogaḥ karmasu kauśalam” (Yoga is skill in action).

One must perform actions in such a way that one remains free from the bondage that actions usually entail. The cause of bondage is the impurity of the mind (citta-malinatā), which arises from the desire for results (phalākāṅkṣā). It is this very desire that taints the mind. Whether one attains the result or not, the mere expectation of it corrupts the mind. Therefore, one must renounce the sense of doership while performing actions. This is called yogastha karma—action performed while established in yoga. In this state, there is no attachment; success and failure are viewed with equanimity. This is samatva-yoga (the yoga of equanimity).

By continuously engaging in action with such an attitude, the mind becomes purified. In this state, the ego weakens, and the power to act diminishes. The self (ātman) experiences a sense of incapacity. Even though the ego weakens, a trace of it still remains. To dissolve this trace, action remains necessary. At this point, rather than thinking about what else to do, one should take refuge in the Supreme Lord (Parameśvara). This is called śaraṇāgati (surrender).

On the other hand, this is also known as sannyāsa (renunciation). One ceases to engage in any form of action and keeps their focus solely on the Supreme Being. To remain constantly attentive to Him is the characteristic of śaraṇāgati. By continuously doing so, action gradually falls away. As long as the slightest sense of ego remains in the heart, one must continue to act. When the surrendered aspirant fully accepts the Lord as their sole refuge in every aspect, the sense of doership ceases. At this stage, the Divine itself assumes the role of the doer:

“Tvayā Hṛṣīkeśa hṛdi sthitena

yathā niyuktosmi tathā karomi.”

(“O Hṛṣīkeśa, You are situated in my heart; as You direct, so I act.”)

At this point, the aspirant realizes that the true inspirer and doer is none other than the indwelling Lord (Antaryāmin Bhagavān). When this realization dawns, the sense of individual agency disappears, and the aspirant attains a state of absolute ease and surrender. The Divine itself then manifests as the sole doer. The aspirant no longer perceives themselves as being externally influenced to act; instead, they remain as a witness (sākṣī), an observer (draṣṭā), while the Divine alone performs all actions.

In this state, the aspirant experiences that whatever actions are occurring through their body, mind, and intellect, are actually being performed by the Divine. Freed from the distinctions of righteousness and unrighteousness (dharma-adharma), they fully surrender at the feet of the Lord and behold His infinite divine play (līlā).

From an ordinary perspective, action precedes grace (kṛpā). However, it must be remembered that grace is present at the root of action itself, albeit in a subtle form. True grace manifests fully only when the aspirant, like a tranquil infant, surrenders themselves at the feet of the Lord with the attitude of a mere observer (draṣṭābhāva).

The Tantric Perspective on Grace and Action

From the perspective of Āgama scriptures, the ancient Tantrikas state that one must rely on appropriate means (upāya) to attain the goal (upeya). Ego manifests in multiple forms—such as identification with the body (dehābhimāna), vital force (prāṇābhimāna), senses (indriyābhimāna), intellect (buddhyabhimāna), and mind (manobhimāna). To transcend these forms of ego, action is necessary. Through specific actions, each corresponding form of ego is pacified. When ego is dissolved, even the impulse to act ceases. Beyond this, the aspirant no longer requires the guidance of scriptural injunctions (vidhi-niṣedha).

How does this transformation occur? It happens when the inner cit-śakti (power of consciousness), dormant since beginningless time, awakens. This is the preliminary state of prabuddhabhāva (the awakened state). In worldly terminology, it is known as Kuṇḍalinī-jāgaraṇa (the awakening of Kuṇḍalinī). Once the power of awareness (saṃvit-śakti) is awakened, the aspirant no longer needs to exert effort on their part. A residual sense of body-identification may remain, but action persists only in a nominal sense.

As the awakened Śakti ascends upward, the inert aspect of existence (acit-sattā) transforms into a conscious essence (cid-ātmakatā) and ultimately merges with cit-sattā (pure consciousness). Just as the Ganges, breaking through icy barriers, flows toward the ocean, the aspirant too, through the force of the Mahāśakti (Supreme Power), advances toward the ocean of consciousness. No additional effort is needed for this; the aspirant becomes active through the movement of Śakti. In this manner, the individual soul (jīva) unites with the absolute (Śiva), reaching the brahma-rūpa (divine essence). Just as the Ganges, upon merging with the ocean, assumes the nature of the ocean, so too does the individual being (jīva) attain Śivatva (divinity).

Three Approaches to Spiritual Attainment

For a novice aspirant (kaniṣṭha adhikārī), the spiritual path necessitates both grace and action (kṛpā and karma) as atomic measures (āṇava-upāya). For an intermediate aspirant (madhyama adhikārī), the Śākta-upāya (the path of Śakti) is more suitable. As stated in the Bhagavad Gītā:

“Sarvadharmān parityajya

Mām ekaṁ śaraṇaṁ vraja.

Ahaṁ tvā sarvapāpebhyo

mokṣayiṣyāmi mā śucaḥ.”

(“Abandon all duties and surrender unto Me alone. I shall deliver you from all sins; do not grieve.”)

Even here, full realization does not occur without Śāmbhava-upāya (the Śiva-path). One may attain Śivatva (the state of Śiva), but realization remains incomplete until one perceives oneself as Śiva. The moment this realization occurs, one attains pūrṇatva (completeness). In this state, both being (sattā) and awareness (bodha) coexist, giving rise to bliss (ānanda).

Simply stated, following the guidance of a guru or scriptures in action is necessary. Through niṣkāma karma (desireless action), the mind becomes purified, and then one must advance with the support of the Supreme Power (Parameśvarī Śakti). This is called kṛpā (grace). Finally, one must establish oneself in one’s true nature (svarūpa), remaining steadfast in self-awareness.

It is noteworthy that kṛpā and karma are interdependent. Initially, action is predominant, and ultimately, grace prevails. In the final state, neither action nor grace remains. Some aspirants experience grace after engaging in action, while others are drawn into action through grace. This variation is determined by the impressions (saṃskāras) accumulated over multiple lifetimes.

The unique characteristic of Mahākṛpā (supreme grace) is that it draws the Divine close to the aspirant, just as a mother rushes to her crying child.

Grace and Action in the Path of Spiritual Attainment Read More »