The Divine Experience of Kāśī as Witnessed by Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa and Others

The Divine Experience of Kāśī as Witnessed by Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa and Others

In Śrī Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Līlāprasanga, written by Swami Sharadānanda, a profound experience of Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa in Kāśī is narrated.

One day, Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa, accompanied by Madhur Bābū (son-in-law of Rani Rāsmani), set out on a boat ride along the Ganges to visit the sacred sites of Kāśī, including Manikarnika Ghat. This ghat is adjacent to the main cremation ground of Kāśī, where funeral pyres continuously burn.

Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa’s Mystical Vision at Manikarnika Ghat

As the boat reached Manikarnika, Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa observed the rising smoke, the flames consuming the dead bodies, and instantly entered into a divine ecstatic state (samādhi). Overwhelmed with spiritual bliss, he jumped out of the boat and ran to the riverbank, standing motionless in deep meditation (dhyāna).

- The boatmen and attendants panicked, fearing he might fall into the water, but soon realized that his body remained steady, unaffected by external movements.

- An extraordinary divine glow and smile radiated from his face, illuminating the entire area.

Madhur Bābū, along with his nephew Hṛiday, carefully stood beside him, while others, including the boatmen, watched in awe at this supernatural event. After a while, when Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa emerged from his deep spiritual absorption, the group proceeded to Manikarnika Ghat, performed rituals, and continued their pilgrimage.

The Divine Revelation of Śiva and Mahākālī at Manikarnika

Later, Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa shared his extraordinary vision with Madhur Bābū and others:

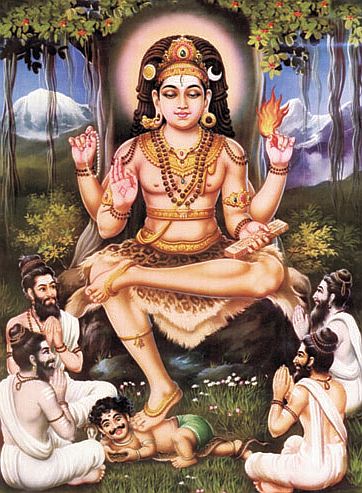

“I saw a tall, radiant white figure with matted hair (jaṭā), walking solemnly through the cremation ground. This majestic Śiva-like being approached each burning pyre, gently lifted the departing soul, and whispered the Tāraka-Brahma Mantra into its ear, granting instant liberation (mokṣa).

At the same time, Jagadambā (Divine Mother) in Her Mahākālī form sat on the other side of each funeral pyre. With Her divine power, She untied the knots of the soul’s attachments to the gross, subtle, and causal bodies, releasing it from all karmic bonds and guiding it toward the eternal spiritual realm (Akhanda Dhāma).

I saw Śrī Viśvanātha (Śiva) compassionately bestowing the highest non-dual bliss (advaitānubhava) upon the departed souls, an experience that takes lifetimes of yoga and austerity to attain.”

A scholarly Brahmin, who was accompanying Madhur Bābū, heard this account and remarked:

“The Kāśī Khaṇḍa (section of the Purāṇas) states that Śrī Viśvanātha grants mokṣa to those who die in Kāśī. However, it never explained how this happens. Today, through your divine vision, I finally understand the process!”

Kāśī as a Divine Consciousness, Not Just a Physical Place

Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa never saw Kāśī as merely a city of stone and temples. He experienced it as a realm of divine consciousness—a living presence of Śiva and Śakti. Many great yogis who have meditated in Kāśī have reported similar mystical realizations.

One such remarkable experience was narrated by a highly respected practitioner (sādhaka) to the scholar Pandit Gopināth Kavirāj. The sādhaka, having renounced worldly life, had settled in Kāśī and shared his personal account:

A Mysterious Encounter with a Divine Sage at the Time of Death

In 1605 CE, a young boy named Vijay arrived in Kāśī from Bengal. Over time, he became deeply connected with the sādhaka, and they often walked together in the evenings.

About a year later, Vijay’s elderly relative (his uncle’s father) wrote to him, informing that he was terminally ill and wished to spend his final days in Kāśī. Soon, the family arrived, and a house was rented near Teḍhī Nīm to accommodate them.

The elderly man’s health did not improve, but he felt an inexplicable sense of inner peace after arriving in Kāśī. As his illness progressed into double pneumonia, doctors warned that he might not survive the night.

A Divine Visitor at the Moment of Death

That evening, as the family members waited anxiously, the sādhaka remained beside the patient while Vijay went home to fetch a physician.

Suddenly, the sādhaka heard the sound of wooden sandals (khaḍāuṅ) approaching from below. As he turned towards the staircase, he saw:

- A radiant sannyāsī (renunciate) entering the room, holding a trident (triśūla) and a water pot (kamandalu).

- The mystical figure approached the dying man, bent over, and whispered something into his ear.

- The old man, unable to move for days, suddenly turned slightly as if attentively listening.

Within moments, he took two deep breaths and passed away.

The Mysterious Identity of the Sage

The sādhaka was stunned and immediately asked the others:

“Who was that sannyāsī? Did you see him?”

To his shock, no one else had witnessed the sage’s presence!

This left him in deep awe and realization—the divine renunciate was none other than Śiva Himself, coming to personally deliver the Tāraka-Mantra and grant liberation!

The Lasting Impact of This Experience

The sādhaka later shared this experience with Mahāmahopādhyāya Pandit Yādaveshvara Tarkasāgara, a renowned scholar.

Hearing this, Pandit Yādaveshvara was so deeply moved that he vowed never to leave Kāśī again, fearing that he might miss the opportunity of receiving Śiva’s final grace at the time of his death.

Since that day, whenever the sādhaka passed by that house, he felt a surge of divine bliss, recalling the sacred moment of the soul’s final liberation through Lord Śiva’s grace.

Conclusion: The Divine Mystery of Kāśī’s Liberation

The sacred narratives of Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa and various enlightened souls confirm that Kāśī is:

- Not just a geographical location, but a spiritual power center where Śiva and Śakti actively liberate departing souls.

- At the moment of death in Kāśī, a divine force lifts the soul beyond the cycle of rebirth.

- Lord Śiva Himself whispers the Tāraka-Mantra, and Mahākālī unbinds the soul from its karmic bonds, granting final emancipation.

Thus, the glorification of Kāśī in scriptures is not an exaggeration but a spiritually verifiable truth experienced by great yogis, saints, and realized souls.

To die in Kāśī is not merely a physical event—it is a spiritual culmination, where death is transformed into an eternal liberation.

The Divine Experience of Kāśī as Witnessed by Śrī Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa and Others Read More »