1. The Opening Dialogue

nārada uvāca –

Nārada said:

atha gāyatrī tantram

nārāyaṇa mahābhāga gāyatrī yāstu samāsataḥ ।

śāntyādikānprayogāṁstu vadasva karuṇānidhe ॥

O fortunate Nārāyaṇa! This is the complete Gayatrī; now, please explain the applications (prayoga) of śānti (peace) and similar rites, O treasure-house of compassion.

(In the narrative, Nārada poses the question: “O Nārāyaṇa, please describe the uses of Gayatrī for peace etc.”)

2. The Lord’s Reply and the Secrecy of the Matter

nārāyaṇa uvāca –

Nārāyaṇa replied:

ati guhyaṃ idaṃ pṛṣṭaṃ tvayā brahytanu-dbhava ।

vaktavyaṃ na kasmāiccid duṣṭāya piśunāya ca ॥

“This matter is exceedingly secret, O descendant of Brahma; it is not to be explained to any wicked or unscrupulous person.”

(Thus Nārāyaṇa warns that such esoteric knowledge should not be divulged to those of impure character.)

3. Rites for Attaining Peace from Ghostly and Planetary Afflictions

atha śāntiryoyuktābhih samidbhir juhuyād dvijaḥ ।

śamī samiddhiḥ śāmyanti bhūtaroga grahādaiḥ ॥

A Brahmin (dvija) should perform the homa using samidhas (ritual oblations) prepared with the aid of śānti; by the oblations known as śamī, the afflictions due to ghosts (bhūta-roga) and adverse planetary influences (graha-ādi) are pacified.

ādrābhiḥ kṣīravṛkṣasya samidbhir juhuyād dvijaḥ ।

juhuyācchakalair vāpi bhūtarogādi śāntaye ॥

Likewise, with the moist (ādrābhiḥ) samidhas of the milk tree (kṣīravṛkṣa), the Brahmin should perform the homa; even if using those prepared in another (chakala) manner, the rites serve to pacify ghostly maladies and similar afflictions.

jalena tarpayet sūrya pāṇibhyāṁ śāntimāpnuuyāt ।

jānuśne jale japyā sarvān doṣān śamaṁ nayet ॥

By offering water as a libation (tarpana) to the Sūrya (Sun) with one’s hands, peace is attained; and by standing in water up to the knees (jānuśne) while reciting the mantra, all faults or defects (doṣa) are dispelled.

kaṇṭhadaghne jale japtvā mucyēt prāṇāntakā bhayāt ।

sarvebhyah śāntikarmabhyō nimanyāpsu japah smṛtaḥ ॥

Reciting the mantra in water up to the throat (kaṇṭha-daghne) frees one from the fear of the termination of life (prāṇānta); therefore it is prescribed that to attain complete peace one should perform japa (mantra recitation) while immersed in water.

4. Instructions Concerning the Homa Vessel and Purification

sauvṛṇe rājate vāpi pātra tāmramaye ’pi vā ।

kṣīravṛkṣamaye vāpi niścidre munmaye ’pi vā ॥

The homa should be performed using a vessel made of gold (sauvṛṇa), silver (rājata), or even copper (tāmramaya); alternately, one may use a vessel fashioned from the wood of the milk tree (kṣīravṛkṣa) or an unperforated earthen (mṛnmaya) vessel.

(The accompanying commentary specifies that such a vessel is to be employed for offering the “pancagavyam” (the five sacred substances) and for igniting the fire with wood from the milk tree.)

pratyāhutiṁ spṛśakṣaptvā tad gavyam pātrasanistitam ।

tena taṁ prokṣayed deśaṁ kuśair mantram anusmaran ॥

After each oblation, one must ensure that the sacred “gavyam” (the five offerings) touches the vessel; then, while reciting the mantra, one should cleanse the entire area (deśaṁ) with kusha (sacred grass).

baliṁ pradāya prayato dhyāyet paradevatām ।

abhicārasam utpannā kṛtyā pāpaṁ cha naśyati ॥

After offering the bali (sacrificial oblation) to the deities, one should meditate upon them; thus, sins arising from illicit practices (abhicāra) are destroyed.

devabhūtapishācād yady evaṁ kurute vaśe ।

gṛhaṁ grāmaṁ puraṁ rāṣṭra sarvaṁ tebhyō vimucyate ॥

By subjugating the devata, bhūta, and piśāca through this method, one causes them to relinquish their hold over houses, villages, towns, and even entire regions.

5. The Inscription of the Sacred Symbol in the Mandala

catuṣkoṇe hi gandhena madhyato raciten cha ।

nikhanenmucyate tebhyo nikhanenmadhyato ’pi cha ॥

When a sacred emblem (such as a śūla) is inscribed within a quadrilateral (catuṣkoṇa) using fragrant substances from the center, the malevolent entities are liberated by means of chiseling (nikhanana); even if the chiseling is effected from the very middle, they are set free.

maṇḍale śūlamālikhya pūrvoktē cha krame ’pi vā ।

abhimanya sahasraṁ tat nikhanet sarva śāntaye ॥

In the circular mandala, after inscribing the śūla as prescribed earlier, one should chisel it a thousand times to ensure the attainment of complete peace.

6. Preparation of a Sacred Vessel Filled with Consecrated Water

sauvṛṇaṁ, rājataṁ vāpi kumbha tāmramayaṁ cha vā ।

mṛnmayam vā navaṁ divyam sūtravēṣṭitamavrāṇam ॥

One may use a kumbha (vessel) made of gold, silver, copper, or earthenware—or even a new, divine vessel adorned with a sacred thread (sūtra-vēṣṭita) and lacking any perforations.

maṇḍile saikate sthāpya pūrayēn mantritaiḥ jalaiḥ ।

digbhya āhāty tīrthāni caturasṛbhyaḥ dvijottamaiḥ ॥

This vessel is to be placed within the mandala and filled with water that has been sanctified by mantras; thereafter, by invoking sacred pilgrimage sites (tīrthāni) from the four cardinal directions through the agency of the most excellent Brahmins (dvijottamaiḥ), its power is augmented.

7. The “Gopaniyā” (Secret) Gayatrī Tantra

elā, candana, karpūra, jāti, pāṭala, mallikāḥ ।

vilvapatraṁ tathākrāntāṁ, devīm brīhi yavānstilān ।

sarṣapān kṣīravṛkṣāṇāṁ pravālāni cha nikṣipet ॥

Take the following items: cardamom (elā), sandalwood (candana), camphor (karpūra), jāti, pāṭala, and jasmine (mallikā); also, take bilva leaves (vilvapatra) and those that have “passed” (tathākrāntāṁ), the goddess Devī, brīhi, barley (yavān), and sesame (tilān); further, deposit mustard seeds (sarṣapān) and the coral-like matter of the milk tree (kṣīravṛkṣāṇāṁ pravālāni).

sarvamevaṁ vinikṣipya snātaḥ samāhito vipraḥ sahasraṁ mantrayed budhaḥ ।

kuśakūrchasamanvitam ॥

Having deposited all these, after bathing (snātaḥ) and becoming composed (samāhito), the wise (vipraḥ) should recite the mantra a thousand times, while being attended by kusha arranged as a seat.

dikṣu saurān adhīyīran mantrān viprāstra yividhaḥ ।

prokṣayetyāyayedenam nīraṁ tena abhisiṁchayet ॥

The Brahmins, well versed in the threefold (trayī) recitations of the mantras in all directions (dikṣu), should employ this consecrated water to anoint (abhisiṁchayet) the afflicted individual.

bhūt roga abhicārebhyaḥ sa nirmuktaḥ sukhī bhavet ।

abhisekena mucyeta mṛtyorāsthagato naraḥ ॥

By this anointment (abhisheka), one is freed from the maladies due to ghostly influences and other afflictions, attaining happiness; even a person on the verge of death is saved.

gudūcyāḥ parva vichchhinnaiḥ juhuyād duddha-siktakaiḥ ।

dvija mṛtyunjayo homaḥ sarva vyādhivināśanaḥ ॥

By performing the homa with the offerings of Gudūcyā—which are either broken (vichchhinnaiḥ) or soaked in milk (duddha-siktakaiḥ)—a Brahmin’s mṛtyunjaya homa (that which conquers death) becomes an all‑disease–destroying rite.

8. Prescriptions for Averting Decay, Illness, and Other Afflictions

(The following verses describe various ritual procedures whose details are given in brief; note that the complete methods involve elaborate rules and procedures not set forth here for reasons of secrecy.)

[a] In one procedure, by offering paya (a sweet, milk–based pudding) with repeated oblations and by burning it (thus “sacrificing” it), the process destroys the “kṣaya” (disease of decay). Similarly, by performing a homa with the three substances—milk, curd, and clarified butter (madhutritaya)—the affliction known as Rājayakṣma is destroyed.

[b] In another prescription, one offers food to the Sun (Bhāskara) in the form of paya before the homa and then feeds it to a woman who has observed her prescribed seasonal bath (ṛit snātā); by this act, one is assured of obtaining a son described as a precious gem (putraratnam).

[c] Performing homas with specific types of wood or oblations also yields various boons:

- With the oblations of the milk tree (kṣīravṛkṣa), one attains increased longevity.

- By offering a homa for a month using a hundred lotuses (padmaśataṁ māse), one may acquire a kingdom.

- With oblations made from a mixture including yava (barley) and similar substances (śālisamanvita), one may obtain a village.

- Using the oblations of the ashwā (aśvaya samidha), victory in battle is assured.

- With those of the ark tree (arkasya samidha), victory is attained in all endeavors.

[d] Further, by combining paya with leaves, flowers, or even with the petals of the vetasa (or betel) tree, and offering a hundred such oblations daily for a week, rain (vṛṣṭi) is invoked. Standing in water up to the navel (nabhidāne jale) and performing japa for a week brings rain; yet performing a hundred homas in water with ashes (bhasma) averts excessive rain.

[e] By performing a homa with paya, one gains intellectual prowess (medhā), and by drinking the consecrated substance, one becomes endowed with superior wisdom—even among the gods and Brahmins.

[f] Daily recitation (japa) of a thousand mantras in the proper manner yields longevity and strength, while continuing the practice over a month confers the highest vitality. Specific prescribed counts are given:

- A month’s recitation of 300 mantras per day grants all desired attainments.

- A Brahmin who, standing on one foot with raised arms (dhvānilaṁ vaśī), recites 100 mantras daily for a month, obtains his desired object.

- Reciting the mantra in a prescribed nocturnal mode while partaking in a prescribed meal (havishyānna) for one week confers the status of a rishi; extending the practice for two years makes one’s speech infallible.

- Three years of such practice is said to bestow “trikāl darśana” (the vision of past, present, and future), and four years of recitation results in the divine approaching the devotee.

- Purification through prāṇāyāma followed by a month-long daily recitation of 3,000 mantras liberates one even from the gravest sins.

- For offenses such as trespassing into forbidden regions (agamya gamana), theft, killing, or consumption of prohibited items, recitation of 10,000 Gayatrī mantras is prescribed for purification.

- A person who resides in a forest and recites a thousand mantras daily obtains the merit of a fast; reciting three thousand mantras yields even greater merit.

- It is stated that reciting 24,000 mantras accrues a merit comparable to a certain prescribed measure (kṛccha), while 64,000 recitations are equal in merit to the observance of the Chandrāyaṇa fast.

9. Instructions on Recitation Postures and Their Results

ekapādo japedūṁ bāhū dhvānilaṁ vaśī ।

māsaṁ śatam avapnuyāt yadi cchedhet iti kauśikaḥ ॥

By standing on one foot (ekapādo), with one’s arms raised as if reaching the sky (dhvānilaṁ vaśī), and by reciting 100 mantras daily for a month, one obtains that which is desired (yadi cchedhet)—this is stated by Kauśika.

naktam aśnanna haviṣyānnaṁ gīramocca bhaved enena japtvā

samvatsara dvayam ।

Likewise, by performing japa in the prescribed nocturnal manner (after partaking of havishya food), one becomes a rishi within one year; if this practice is continued for two years, one’s speech becomes infallible.

trivatsaraṁ japed evam bhavet tat traikāl darśanam ।

āyāti bhagavān devacatutah samvataram japed ॥

Reciting in this prescribed manner for three years confers the vision of the three times (past, present, and future); if one continues for four years, the Divine, accompanied by the four Vedic deities, will approach the devotee.

muktāḥ syūradhavyūhācya mahāpātakino dvijāḥ ।

trisāhasraṁ japen mārśa prāṇānāyamya vāgmatḥ ॥

A Brahmin who, after purification by prāṇāyāma, recites 3,000 mantras daily for a month is freed from even the gravest sins.

agamya gamanasteye hanane ’bhakṣya bhakṣane ।

daśasāhakṁ madhyastā gayatrī śodhayet dvijam ॥

For transgressions such as venturing into forbidden places, theft, killing, or the consumption of prohibited foods, the Brahmin is instructed to recite the Gayatrī mantra 10,000 times for purification.

sahasram abhya sanna mārśa nityaṁ japi vane vasan ।

upavāsa-samo japet sahasraṁ taditūchaḥ ॥

One who, while living in the forest, practices a daily recitation of 1,000 mantras is freed from all impurities; similarly, 3,000 recitations confer the merit equivalent to that of a fast.

catuḥviṁśati sahasram abhya-sta kṛcchrasañjñitā ।

catuṣaṣṭi sahasrāṇi cha chāndrāyaṇasamānitā ॥

Reciting 24,000 mantras accrues a merit comparable to that of the “kṛccha” (a prescribed religious observance), and 64,000 recitations are equivalent in merit to the Chandrāyaṇa fast.

10. The Ācāra (Conduct) and Its Supreme Importance

ācāraḥ prathamo dharmo dharmasya prabhurīśvarī ।

ityuktaṁ sarvaśāsveṣu sadācāra-phalaṁ mahat ॥

Conduct (ācāra) is declared to be the foremost dharma, and the Goddess—the very mistress of dharma—is extolled; indeed, all scriptures agree that the fruit (phala) of good conduct is most excellent.

ācāravān sadā pūtaḥ, ācāravān sadā dhanyaḥ ।

satyaṁ satyaṁ ca nārada ।

sadaivācāravān mukhaḥ ।

A man of proper conduct is ever pure and blessed; as Narada says, “Truth, truth” (i.e. one must always speak the truth); a person of good conduct is ever spotless and happy.

devīprasāda janarka sadācāra-vidhānkam ।

āvyet śrṇuyānm matyoḥ mahāsampati-saukhyabhāk ॥

He who listens to and imparts the instructions regarding good conduct—the boon (prasāda) of the Goddess—attains wealth, prosperity, and great happiness.

japyam trivarga saṁyuktaṁ gṛhasthena viśeṣataḥ ।

munināṁ jñāna-siddhyartha yatīnāṁ mokṣa-siddhaye ॥

The recitation of the Gayatrī (japa) performed by the householder (gṛhastha) in conjunction with the three classes (tri-varga) yields the fulfillment of all desires; for sages (muni) it confers siddhi (attainment of knowledge and powers) and for ascetics (yatī) it is the means to liberation (mokṣa).

savyāhṛtīkā sa praṇavāṁ gāyatrī śirasā saha ।

ye japanti sadā teṣāṁ na bhayaṁ vidyate kycit ॥

Those who recite the Gayatrī along with the sacred syllable (praṇava “om”) and with the head (śirasā) remain without any fear whatsoever.

abhīṣṭa lokam avapnuyāt, prāpnuyāt kāma-bhīpsitam ।

gāyatrī vedajananī, gāyatrī pāpa-nāśinī ॥

By this recitation, one obtains the desired world; Gayatrī is revered as the mother of the Vedas and the destroyer of sin.

gāyatrī japyam niratam svargam āpnuyāt mānavaḥ ।

gāyatrī japyam niratam mokṣopāyaṁ ca vindati ॥

He who constantly recites the Gayatrī attains heaven, and through continuous recitation, he also discovers the path to liberation.

tasmāt sarvaprayaṭtena snātaḥ prayatamānasaḥ ।

gāyatrīm tu japet bhaktayā, sarva-pāpa praṇaśinī ॥

Therefore, after bathing and with a determined mind, one should recite the Gayatrī with devotion—she is the annihilator of all sin.

sarvakāma pradā caiva sāvitri kathitā tat ।

abhicāreṣu tāṁ devīm viparītāṁ vichantayet ॥

Sāvitri, who is said to bestow all desires, is to be contemplated in a manner opposite to that appropriate for illicit practices (abhicāra).

kāryā vyāhṛtayāśvaitr, viparītākṣarāstathā ।

viparītākṣara kārya, śiraś ca ṛṣisattama ॥

For the performance of ritual acts (kārya), one should pronounce the sacred syllables in an “inverted” (viparīta) manner; even the syllable corresponding to the head (śira) is to be so pronounced, O best of sages.

ādau śiraḥ prayoktavyam, praṇayo ’nte vai ṛye ।

bhīti-sthenaiva phaṭ-kāraṁ makhya nāma prakīrtitam ॥

At the beginning, the “śira” (head syllable) is to be used; at the end, the praṇava is to be recited; and in the middle, the sound “phaṭ” (known by the name “Makhya”) is to be pronounced.

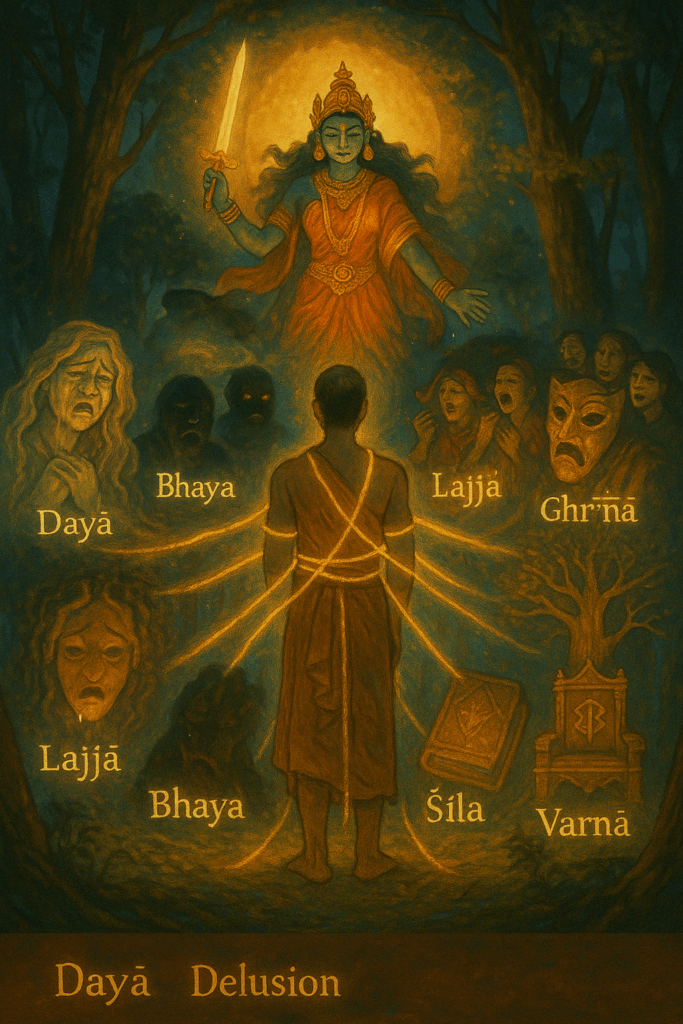

gāyatrī cintayet tatra dīptānalasamaprabham ।

ghātayantīṁ triśūlena keśeṣvāksipya vairiṇam ॥

Contemplate the Gayatrī there, whose effulgence is like that of a blazing fire; envision her striking down the enemies by seizing their hair with her trident (triśūla).

evaṁ vidhā ca gāyatrī japtavyā, rājasattama ।

hotavyā ca yathā śaktya, sarvakāma-samṛddhidā ॥

Thus, the Gayatrī must be recited by the person of highest quality (rājasattama), and the homa is to be performed according to one’s capacity (śaktya) to bestow the fulfillment of all desires.

nirdahantī triśūlena, dhakuṭī bhūṣitānānām ।

ucchvāṭane tu tāṁ devīm, vāyubhūtāṁ vichintayet ॥

One should meditate upon the Goddess—who, with her trident, burns (nirdahantī) the adversaries whose ornaments (bhūṣitānām) are thus overcome—and at the moment of her “raising” (ucchvāṭane), one should contemplate that airy (vāyubhūtāṁ) form of the Goddess.

dhāvamānam tathā sādhyaṁ, tasmat deśāt tu dūrataḥ ।

abhicāreṣu hotavyā rājikā, viṣam-amiśritāḥ ॥

Those who are in rapid motion (dhāvamānam) as well as that which is to be attained (sādhyaṁ) should be approached from afar; and in cases of illicit practice (abhicāra), the royal (rājika) element is to be mixed with poison.

svarakta-miśraṁ hotavyam, kaṭuta-tailam athāpi vā ।

tatrāpi cha viṣaṁ deyaṁ, homa-kāle prayatnatāḥ ॥

A mixture of blood (svarakta) with bitter oil (kaṭuta tailam), or any similar preparation, must be offered—indeed, even there, one should deliberately offer poison (viṣa) at the time of the homa.

mahāparārtha balinaṁ deva-brāhmaṇa-kaṇṭakam ।

abhicāreṇa yo hanyāt, na sa doṣena lipyate ॥

One who, by means of abhicāra, slays a powerful offender—one who inflicts harm (kaṇṭaka) upon the gods and Brahmins—does not incur sin.

bahūnām kaṇṭakātmān, pāpātmān sūdummatīm ।

hanyāt kṛtāparādhattantu, tasya puṇya-phalaṁ mahat ॥

And whoever destroys such a wicked, sin–laden being—one who has become an obstacle in the paths of many—acquires an exceedingly great fruit (puṇya-phala) for the act of slaying.

(A concluding note explains that the above indicate only a few of the “minor” ritual applications prescribed in the Gayatrī Tantra for subjugating a sinful or wayward person. The complete details—comprising elaborate procedures, ritual operations (karma-kāṇḍa), and regulations (niyama-bandha)—are not recited here for it is considered unwise to disclose such secret matters to the general public, as this might disturb public order. Nevertheless, one who engages in such an act against an offender attains immense merit.)