Gati-Sthiti (Movement and State)

What is “Gati” (Movement) and “Sthiti” (State)?

The term “gati” refers to movement or motion, specifically the transition phase of a journey. In the scriptures, there is mention of two primary paths or movements after death:

- Devayāna Gati (Path of the Gods)

- Pitṛyāna Gati (Path of the Ancestors)

The Pitṛyāna Gati extends only up to the lunar realm (Chandraloka). After experiencing the fruits of past actions in that realm, the soul must return to the cycle of birth and death. This is why it is considered a circular or curved movement (vakragati).

In contrast, Devayāna Gati leads towards the solar sphere (Sūryamaṇḍala). Upon crossing the solar sphere, the soul merges into the eternal Brahman and does not return. This is a straight or direct movement (sarlagati). The scriptures widely acknowledge both types of movements.

The Pitṛyāna Gati is associated with souls destined for rebirth. Those who take this path do not stay permanently in any celestial realm; they are bound to return, whether from heaven or any other loka, to resume their journey through human birth and karma. The cycle of ascent and descent continues for such souls.

In contrast, Devayāna Gati cannot be attained without the integration of knowledge (jñāna) with action (karma). While absolute knowledge (viśuddha jñāna) is not mandatory, the harmonization of knowledge and action is essential for Devayāna Gati.

The Role of Bhakti and Yogic Disciplines

Devayāna Gati has been extensively discussed by bhakti-oriented traditions and spiritual masters. Apart from describing this path, they have also elaborated on the process of soul’s departure at the time of death, known as utkramaṇa.

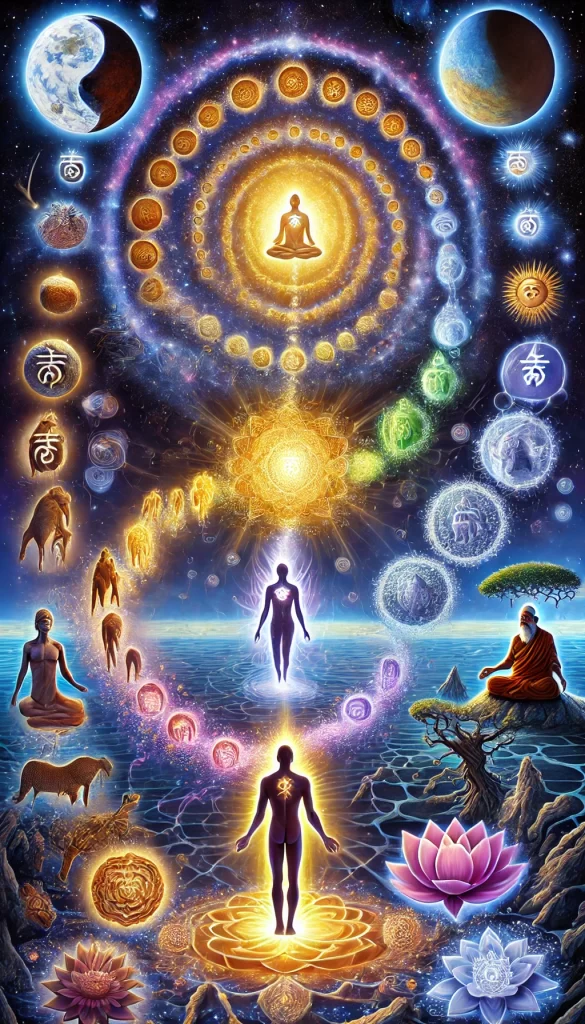

One of the key spiritual pathways for liberation is Sushumnā Nāḍī, the central energy channel in the human body. Just as the Sushumnā Nāḍī exists within the body, there is a cosmic Sushumnā pathway in the universal structure, extending beyond the human body.

Sushumnā is considered a radiant solar energy channel, or a ray of the Sun. If at the moment of death, the departing soul is able to ascend through this pathway, it reaches Brahmaloka—the highest celestial realm—without returning. This is Devayāna Gati, which leads to complete liberation (mokṣa), without the possibility of rebirth.

The State Beyond Movement—The Ultimate Stillness

There exists a state where there is no movement at all. This state is not for everyone; only those who attain complete spiritual realization remain in an unchanging state of divine union with the Supreme (Paramātman). This is the state of final integration (Yoga-siddhi), achieved by great bhaktas and yogis.

If knowledge is fully developed, movement ceases to exist because the necessity for transition disappears. Movement exists only as a means to progress from lower to higher states. But once the highest state is attained, there is no returning nor moving forward—only permanent beingness in the Absolute.

The Three Fundamental States of Movement

- “Gati-Aagati” (Coming and Going) – The soul moves upwards but returns due to unfinished karma. This is the Pitṛyāna path, bound to the cycle of birth and death.

- “Gati without return” – The soul ascends but does not come back, reaching a state of permanent residence in the divine realm (Devayāna).

- “Neither coming nor going” – The ultimate transcendental state where movement is not required, as the being has already attained oneness with the Supreme.

The Ultimate Realization

The highest teaching of this doctrine is that once the soul comprehends its true nature, it no longer needs to seek any other realm. The Supreme Reality (Brahman) is omnipresent, and the idea of a journey itself dissolves.

For those still in spiritual progression, moving towards higher realms is necessary until final liberation is attained. But for fully realized beings, movement has no significance.

Thus, the mystery of movement and stillness (gati-sthiti) lies in understanding the path of return, the path of no return, and the state beyond all movement.

Gati-Sthiti (Movement and State) Read More »