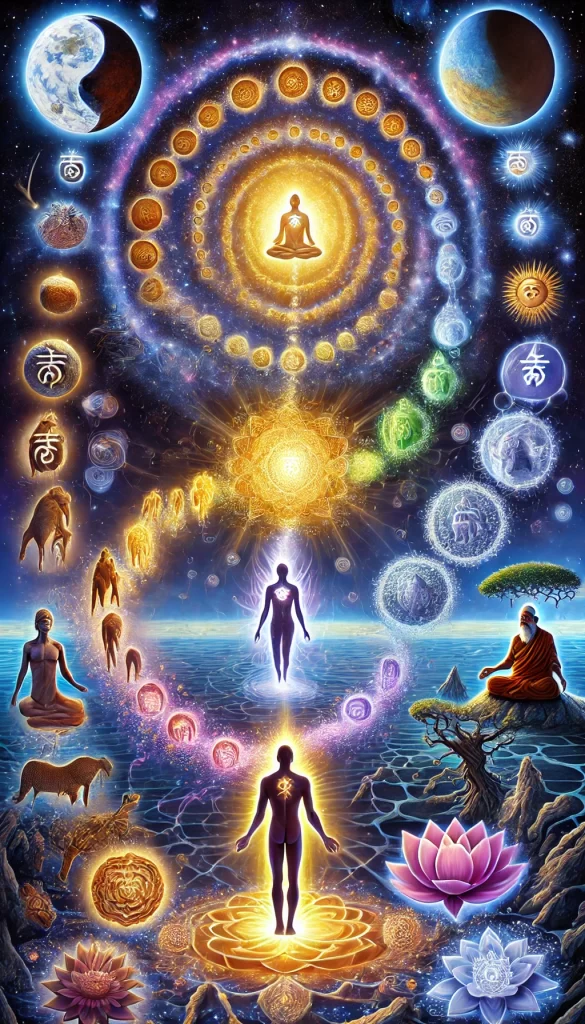

First Journey: Renunciation of Inertness and Attainment of Human Consciousness

In the first journey, the soul renounces its inert state and attains human consciousness. In the second journey, it transcends human consciousness and attains divine consciousness. In the third journey, having immersed itself in the divine consciousness, it explores the infinite diversity of existence.

The Supreme and Complete Self manifests from the divine and cosmic existence. At the root of this manifestation lies the resolution of the supreme self-luminous consciousness. When the divine existence develops the intent to know itself, the soul and the universe sequentially emerge.

Initially, the soul radiates from the infinite and indivisible supreme existence in the form of “Aham” (I), and simultaneously, its counterpart “Idam” (This) appears as the opposing principle, often referred to by various teachers as Purusha (conscious principle) and Prakriti (material principle). The soul, as Purusha, gradually integrates with Prakriti and progresses along the path of evolution.

Here, it must be remembered that the soul is eternal and conscious, whereas Prakriti is non-conscious (Achit). In the state of manifestation, Chit (consciousness) and Achit (non-conscious matter) exist as an undifferentiated reality. The non-conscious principle (Achit) is conceptualized as the embodied form of the Aham-rupa (egoic) soul. Initially, it remains in an indistinct form, but gradually it takes on more defined forms, evolving into bodily structures that merge with the experiencing soul. This constitutes the evolutionary sequence of 8.4 million life forms.

Within this sequence, beings emerge from static existence (Sthāvara) to mobile existence (Jangama). Even within these categories, there exist hierarchical progressions. Eventually, the human form is born, marking the first phase of Prakriti’s evolutionary expansion.

Evolution of Human Consciousness

In this evolutionary process, the first development occurs at the level of Annamaya Kosha (food sheath), followed by the emergence of Pranamaya Kosha (vital sheath). The signs of Manomaya Kosha (mental sheath) begin to appear in non-human creatures. However, it is only upon the complete development of the mental sheath that the human body emerges.

While non-human beings exhibit traces of mental faculties, they do not possess a fully developed mind. The emergence of Manomaya Kosha and the birth of the human body are primary and crucial outcomes of Prakriti’s transformation. In the realm of the mind, the development of six chakras occurs, granting humans the faculty of discriminative intelligence (Viveka), enabling them to act with moral responsibility.

It is only in the human body that an ethical life is possible. Among animals and birds, the question of ethics does not arise because they lack the necessary discriminative faculty (Viveka). The complete development of Manomaya Kosha occurs solely within the human body, making righteous and unrighteous actions (Dharma-Adharma) meaningful.

In this state, the soul assumes a doership identity (Kartutvabhimana), leading to the accumulation of Karmic fruits (Karma-Phala). It must be remembered that the results of moral and immoral actions manifest as pleasure and pain. In non-human forms, the soul neither acts nor experiences, but upon attaining a human body, it assumes both roles—as an actor (Karta) and an experiencer (Bhokta).

In truth, will (Ichchhā) arises only in the human body. However, it must be noted that after attaining a human body, the development of human nature takes time. Initially, humans retain animalistic tendencies, lacking the valiant disposition necessary for spiritual ascent.

When an externally human form attains inner human consciousness, both animal and heroic tendencies are transformed into human virtues. The human body alone is capable of realizing the divine, for true divinity emerges only when the fullness of human nature is achieved. The direct emergence of divine consciousness from animalistic tendencies is not possible.

As long as human consciousness remains undeveloped, a person remains bound by Karma. Due to the consequences of past actions, they undergo numerous rebirths, traversing different realms of existence. The force of Karma may cause a person to be born as an animal or bird, merely to experience the results of their past actions. Some souls ascend to celestial realms, but upon exhausting their Karmic fruits, they return to human birth.

After undergoing countless rebirths, the sense of doership gradually weakens, leading to the realization that one is not truly the doer, but rather, an entity influenced by Prakriti. As this realization deepens, one understands that the Supreme Being alone is the true doer, and that all actions are ultimately governed by divine will.

At this stage, renunciation of actions (Karma-Sannyasa) occurs, leading the aspirant to recognize that all actions are performed by the divine, while the soul is merely a witness. This marks the culmination of the first journey—the soul, having emerged from the divine consciousness, travels through 8.4 million life forms, attains a human body, experiences doership, and ultimately transcends the illusion of agency, setting the stage for the second journey.

Second Journey: The Ascent from Human to Divine Consciousness

The second journey begins with renunciation (Vairagya)—a decline in attachment to worldly objects. At this stage, the grace of the divine is received in the form of a Guru, who guides the seeker. Through the awakening of discriminative wisdom (Viveka) and knowledge (Jnana), the aspirant progresses towards divine realization.

Initially, one follows the path prescribed by the Guru or the inner guidance of the indwelling divine presence (Antaryamin). The aspirant gradually transcends the gross body (Sthula Deha), the gross world (Sthula Jagat), the subtle body (Sukshma Deha), the subtle world (Sukshma Jagat), the causal body (Karana Deha), and the causal world (Karana Jagat).

At the final stage, the mind itself is transcended. The seeker first surpasses the Manomaya Kosha, then the Vijnanamaya Kosha (intellectual sheath), and ultimately detaches from the universal mind (Mahamanas).

On the other hand, divine power (Aishwarya Shakti) and divine love (Aishwarya Prema) develop. Once the mind and its modifications dissolve completely, the seeker directly experiences the divine form (Bhagavat Svarupa), realizing “I am That”—“I am God, I am the Master of the universe”.

With the complete realization of the Manomaya Kosha, moral life reaches its culmination. The Vijnanamaya Kosha then transitions into spiritual life, which eventually culminates in Anandamaya Kosha, the sheath of bliss, marking the beginning of divine life. This divine life is the realization of God. With this, the second journey concludes.

Third Journey: The Infinite Exploration of Divine Consciousness

After completing these two journeys, divine realization becomes permanent. However, most philosophical traditions perceive the second journey as the final attainment.

Yet, in Advaita-Shakta philosophy, the ultimate journey is not merely a state of static realization but an eternal progression within the Supreme Shakti. From the dynamic perspective, infinite movement exists within infinite stillness—this is the mystery of the third journey.

Generally, most philosophical schools regard liberation as the cessation of movement, but Shakta philosophy views the final attainment as an ever-evolving, infinite play within the Supreme Consciousness.

The journey is thus not a linear process with an endpoint, but an eternal expansion of divine consciousness—a ceaseless dance of self-exploration within the infinite.

This is the profound mystery of the soul’s journey—a movement from the divine to the human, and ultimately, from the human back to the divine, where it eternally revels in the bliss of infinite existence.